|

The museum of Nubia

plays vital role not only at the

level of promoting Nubia to the entire world but also at the

level of maintaining monuments and supporting researchers,

interested in Nubia, from around the globe The museum of Nubia

plays vital role not only at the

level of promoting Nubia to the entire world but also at the

level of maintaining monuments and supporting researchers,

interested in Nubia, from around the globe

This, however could be achieved through the museum's study

center and the documentation centers which publish more

information on the "Land of Gold" in Egypt, the past, the

present and the future

Nubia Museum, which hosts 3000 monumental

pieces of several times, ranks tenth in the list of the museums

inaugurated in Egypt over the past three years. An array of

important museums, however, has been inaugurated; Mohamed Nagui

Museum, Modern Egyptian Art

Museum, Museum of Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil and his wife, Museum of

Ahmed Desouki, Port Said Museum for Modern Arts, Taha Hussein

Museum, and the Mummification Museum in Luxor.

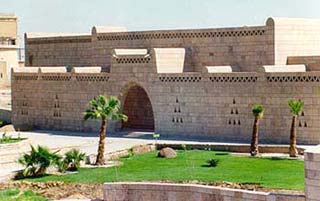

The museum is set on a hill in the cataract region, just beyond

the Cataract Hotel, surrounded by a garden with views of the

surrounding landscape. The building itself is already

spectacular, even beautiful. It was designed by Dr Mahmud

el-Hakim, who was responsible for the design of the Luxor Museum

of Ancient Egyptian Art, which opened in 1975. Its exterior is

decorated in simple forms, entirely executed in the local Nubian

sandstone and suggesting Nubian temple walls. A decorative band

of stones in a zigzag pattern imitates the mudbrick courses of

Nubian house architecture. Different architects were responsible

for the garden and the interior of the building, respectively.

The exhibition inside the museum is arranged in chronological

order, devoting equal space to the different eras of Nubian

history. The museum is devoted to the Egyptian part of Nubia, or

Lower Nubia, which was entirely drowned by the waters of Lake

Nasser, after the building of the Aswan dam. The country no

longer exists, but as a result of systematic archaeological

surveys and excavations, many objects and even entire monuments

were saved. Several museums in foreign countries have in recent

years devoted displays to the history of Nubia, such as the

British Museum and the museums of Boston and Toronto. Now,

finally, Egypt itself has amassed the largest exhibition of all

in Aswan, surrendering to the present-day Nubians their history.

The success of the museum with the local Nubian population is

demonstrated daily by the hundreds of Nubian visitors to the

museum, many of whom now live in the region of Aswan. In fact,

the museum has been designed to be more than just an art

collection and an historical display. On the grounds of the

building, two theatres have been added, and a gallery has been

included for showing contemporary work by Nubian artists. A

library is to be housed in it as well, stimulating the academic

study of the Nubian past.

The display cases of the museum contain over 2000 items, all of

which are well lit and labelled in state-of-the-art show cases.

Efforts have been made to evoke the original surroundings of the

exhibits, which are lost, through the regular insertion of scale

models of buildings from the historical periods represented. At

the start of the exhibition, a large model of the Egyptian Nile

Valley indicates the large number of Egyptian temples which once

stood along the Nubian Nile.

It is entirely fitting that the centrepiece of the entire

display should be a colossal statue of Rameses II, which once

formed part of the rock temple of Gerf Hussein. Many of the

unique Nubian temples were saved during the international

campaign organized by UNESCO in the 1960s, and the remains of

several of these temples were donated by Egypt to the foreign

participants in this campaign. Standing there dwarfed by the

colossal statue of Rameses, one is reminded of the sad fact that

many more monuments have had to be sacrificed. The temple of

Gerf Hussein is one of the pharaonic style temples which could

not be saved, and today only this colossus and some odd

fragments of sculpture and relief remain. These pieces make, to

my mind, a dramatic statement about the scale of the sacrifice

which Egypt made by building the High Dam at Aswan in the

attempt to secure for itself a prosperous future. Likewise, only

a few fragments of the chapel of Horemheb at Abu Oda survive,

and only one of the original four decorated rock chapels from

Qasr Ibrim were included in the museum (the largest shrine, of

Usersatet, from the reign of Amenophis II). The remaining three

chapels had to be abandoned at the base of the cliff, where they

had been carved some 3500 years ago.

The museum presents the history of Nubia in the terms coined for

the history of Egypt. The terms Old, Middle, and New Kingdom are

used throughout, which is rather artificial but it has the

advantage, apart from being familiar terms of reference for the

visitor, of highlighting the intimate association of the Nubian

culture with the Egyptian. The museum displays highlight these

connections specifically. For instance, it includes a copy of

the famous wooden tomb model of a group of Nubian archers in the

Cairo Museum, which was found in Asyut in Middle Egypt, and

which attests to the presence of Nubian soldiers in Middle

Kingdom Egypt.

The history of the town of Aswan itself has also been

incorporated into the museum's displays, and for good reason.

The border town of Aswan has always stood under the influence of

both cultures, as is evidenced, for instance, by the Middle

Kingdom coffin of Heqata (formerly kept in the Egyptian Museum),

who was a Nubian buried in Aswan in the Egyptian fashion. Other,

purely Egyptian artefacts from Aswan are also shown here, such

as the powerful statues from the Heqa-ib chapel and a head of

Nectanebo II found on Elephantine Island.

Another period which is represented in the collection, for

obvious reasons, is the Egyptian Twenty-Fifth Dynasty, during

which the Nubians ruled over Egypt. A number of masterpieces

have been selected dating from this period, both from the

southern capital of Napata (Sudan) and from the area of Luxor.

Thus, we see the 'dream stela' of Tanutamun from Gebel Barkal,

and the beautiful statues of Harwa and of Horemakhet from

Karnak.

As state above, the emphasis in the collection lies on the

region of Lower Nubia. The visitor is first introduced to the

large collection of prehistoric material, with its beautiful

flint tools and rock carvings (petroglyphs). Part of the latter

collection has been effectively displayed inside an artificial

cave in the garden of the museum. Unfortunately, these pieces

have been excluded from the otherwise excellent labelling, and

the numbers and places of origin of the individual pieces are

not clear.

The A-Group and C-Group cultures are introduced mainly through

the effective use of text panels in the display. These cultures

represent the original indigenous way of life of the Nubians

before the Egyptian influence became pervasive. The Egyptians

colonized the region and built massive defence systems during

the Middle Kingdom at its southern border in the Second

Cataract. A model of the fortress of Buhen suggests the large

scale of these structures of mudbrick, of which none could be

saved from inundation. Otherwise, only a small selection of

objects, mainly ceramics, is shown, as well as a reconstructed

A-Group burial.

The most extensive temple building in the region dates to the

New Kingdom, and this remains the best known feature of Lower

Nubia. Recently, a number of cruise ships have started to

traverse Lake Nasser between Aswan and Abu Simbel in order to

allow visits to the temples which have been relocated along the

shores of the lake. In the museum, the subject of temple

building is addressed by the fragments saved from the sites of

Gerf Hussein, Qasr Ibrim, and Abu Oda, already mentioned, as

well as by the contents of a small solar chapel which formed

part of the Great Temple at Abu Simbel. These items, a shrine

with statues, two obelisks, and four baboon statues, were

brought to Cairo after their discovery in 1909.

The labelling is effective, with much additional information

provided in separate text panels on the walls, in both Arabic

and English. For children, the objects themselves will certainly

capture the imagination: for instance, the exotic royal burial

equipment from Ballana, which was formerly kept in the Cairo

Museum. The horse trappings and jewellery from these tombs

continue the tradition of blending the Egyptian and African

artistic styles which already characterises the earlier Meroitic

culture. The Meroitic culture was centred in Sudanese Nubia, and

this important historical phase has, as a consequence, received

only scant attention in the current museum display. Only some of

the famous decorated ceramics from this period are shown and

some of the characteristic funerary statues known as ba-birds.

The Christian and Islamic periods are represented in a small

number of well chosen objects. The delicate church frescos from

Abdallah Nirqi have been transferred here from the Coptic Museum

in Cairo. The Islamic display includes some stunning textiles

from the fourteenth century AD, found at Gebel Adda and Qasr

el-Wizz. These are followed by a lengthy description on a series

of text panels describing the building of the High Dam. Separate

text panels are devoted to the ensuing international rescue

campaign which has yielded so many of the pieces in the museum.

The final section of the museum's tour through Nubian history is

an ethnographic one. The contemporary Nubian folklore is

presented here in a series of life-size dioramas which represent

scenes from village life. During my visits to the museum, the

Nubian visitors were much attracted by this display, which

elicited many remarks of recognition.

The staff of the museum, which is mostly Nubian, numbers about

a hundred people and is under the direction of Dr Sabri Abd

el-Aziz, and the chief conservator Ossama Abd el-Wareth.

|